The lesson from the Resurrection to 9/11 and covid - we have to learn to live again

By locking our doors we lock our hearts, writes George Pitcher. We have to take the risk of going out again.

The other side of this summer, in September, sees the twentieth anniversary of the attacks on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York, a date carved into contemporary history as 9/11.

On that sunny late-summer morning, a group of clergy were meeting for a conference at the nearby Trinity Institute, part of the Episcopal parish of Trinity Church in south Manhattan. When the first plane hit, they thought it was “some cowboy” breaking the sound barrier. They realised something more serious was happening when smoke and burnt paper started floating past the windows on the 22nd floor.

The air became suffocating. The Institute’s director, Fred Burnham, recalls thinking: “Well, it’s worse outside and I don’t know how much longer we can tolerate this… and beginning then to realise I would die.” *

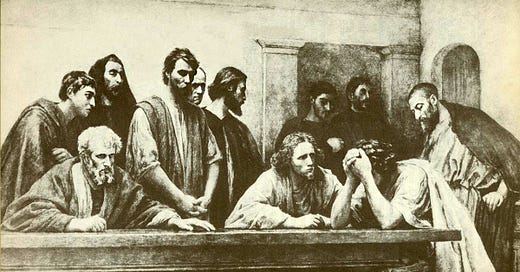

They were, of course, in an upstairs room. Cutting to an entirely different sort of story, I’m reminded by Burnham’s testimony of a much earlier group of disciples, gathered in another upper room, with the doors locked for fear of what a baying mob outside would do to them, when their recently dead leader and teacher suddenly appeared among them to say “shalom aleichem” (“peace be with you”).

And, in turn, I think of that encounter because it resonates with a widespread, perhaps universal, feeling of fear we have about emerging from the rooms in which we have been involuntarily trapped for so long by the pandemic, into what might seem a dangerous and threatening world.

Our rooms may not be locked, but we’ve been shuttered indoors none the less. For many of us lockdown has been a sanctuary, a bolthole away from a world that for a year or more has threatened us with indiscriminate disease and death. We’ve grown accustomed to hiding away, keeping to our own, or if we do venture out then masking up and avoiding human contact, keeping our distance, isolating ourselves.

At the same time, we know this is not what we were designed for. We long to be back at the pub or club, dropping our masks so that we can see smiles, for handshakes and high-fives, even as public-service ads from BBC radio, rather improbably cast as an all too real Ministry of Truth, order us to refrain from hugging.

We grumble because we’re social animals. Being locked down is not our natural state, but by now we’ve been conditioned into an illusion that it is so. In this respect, it’s not unlike a period of war, another unnatural state for us, after which we have to learn to greet one another again in fellowship, as friends, to make our peace - shalom aleichem. Namaste.

Learning to be vulnerable

To do so is not without risk. But risks are what humans take and at their best they take them for each other. So we need to be risk-takers, not just safe-keepers - we need to learn to do that again too. We’ve become accustomed under the covid regime to speaking of the “vulnerable” as though they’re weaker than us, as if vulnerability is something to be avoided (like the plague perhaps). We need to learn to be vulnerable again.

That means, bluntly, learning to put our lives at risk again. Not putting ourselves at risk of death – something that it is reasonable to try to avoid – but it does mean embracing the risks of living. Risking ill-health and hurt and rejection. And the greatest risk of living is to love, for in doing so we make ourselves utterly vulnerable; we put our lives on the line.

To love and to be loved is to expose us to the risk of making ourselves dependent on another. We don’t consider that kind of dependence a weakness, so we really shouldn’t consider being vulnerable as a weakness.

These are things that normally come not as second nature but as part of our first. They are not ingrained habits so much as what we’re designed for. It’s a false state of being into which we’ve been coerced by circumstance over the past year. We’re about to learn what we are again – creatures that not only take joy from being in each other’s company, but which can’t survive without it. For to be isolated is to die.

So we have to vacate our safe upper rooms in order to live and, in doing so, to know freedom. A freedom in this life that was so cruelly denied those in the most hellish of upper rooms that couldn’t be vacated two decades ago – those on the floors above where the planes hit nearly 20 years ago on 9/11.

Defiant witness

But even here, words of love that were uttered, messages that were texted or recorded – and from passengers on the doomed planes themselves – stand in defiant witness of something inextinguishable in the darkness of that day. This was prayer at its purest and most elemental and, perhaps, a glimpse of what perfect freedom looks and sounds like.

Those who did survive that day report being enclosed in a “circle of love”. According to Fred Burnham: “None of us will ever forget it… And I discovered for the first time that I’m not afraid of death and that has totally changed my life.” *

We must learn to be free from fear of death. The freedom to have scampi and chips on a pavement outside a pub from Monday barely competes with that. But the extreme sets the example for the trivial. We should be brave and step out into the unknown next week, take a hand and step into the dark. Because we only make sense in the company of other people, because we’re not made to be trapped, because to love is to be set free and to be fully alive.

George Pitcher is a visiting fellow at the LSE and an Anglican priest

(Fred Burnham is quoted from Rowan’s Rule, Rupert Shortt’s biography of Rowan Williams, who was with Burnham on 9/11)