Nazanin was an exile - she owes her nationhood nothing

The exile is stripped of identity, writes George Pitcher. It's not for us to give it back

To be an exile is to be banished from one’s native land. It’s a penal condition – the exercise of a political power over a person or a people to exclude them from where they belong.

It’s also an act of humiliation and oppression. The exile is made subservient either to the domestic power from which they’re separated or to the host power by which they’re incarcerated. It can apply to whole peoples or to individuals – one thinks of Napolean on St Helena or the Apostle John on Patmos.

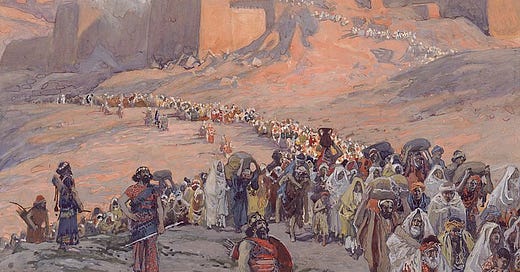

The best known historical and biblical exiles are those of the ancient Jewish people by the Assyrians and the Babylonians and, originally, in Egypt, from which Moses led his people to freedom in their Promised Land.

State of mind

It’s in these that we see exile, too, as a state of mind. Exiles not only have their nationhood confiscated, but their personhood expunged. To be released from that state is to be redeemed, as the tribes of Israel were to a “land flowing with milk and honey”, singing psalms of praise and thanksgiving to their salvific god. They are not only a people again, but people, not slaves.

Which brings me to Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe. She was not exiled by her own country (which it should be unnecessary to affirm – but tragically isn’t always – is Britain), but rather taken captive by a foreign regime and dehumanised as a geo-political asset.

Hebrews’ fate

That kind of captivity is not dissimilar from the Hebrews’ fate in Egypt. And while she was not actually exiled by the government of Britain for six years in Iran, it may be possible to be banished by incompetence and carelessness, to which she referred in her press conference, citing in general five foreign secretaries but refraining from citing one in particular, Boris Johnson, whose indolence in that job almost certainly kept her banged up.

But it’s her mindset – and that of those who have received her home – where there are also exilic resonances. She has hardly been returned to a land flowing with milk and honey, though that may be more than a reasonable metaphor for her reunion with her family. That’s a call for her and them to make – it must be infinitely tougher than the comfy romantic-movie version that the British press project. Certainly more complex than suggesting she’ll have a nice Mothering Sunday this weekend.

She is expected, like a redeemed returning exile, to sing hymns of praise to her native nation, to offer thanks for deliverance. This presupposes that she is a chosen one, privileged among others less fortunate to be plucked from captivity.

Left others behind

This is true only in so far as she has left others behind her in Iran. The rest is to presume that exiles, whatever the nature of their banishment, owe a debt of gratitude to the nation to which they return. It’s that subconscious presumption that has fed the vile social-media hashtags that vilify her as ungrateful and in some way unworthy of release.

Perhaps the worst of that is to assume that her release is also her resolution. That in some way, perhaps again in a sentimental movie climax, being home makes everything all right. Zaghari-Ratcliffe told tellingly in her press conference that she has been “holding this black hole” in her heart. We cannot – as in we are simply not permitted to – consider of what this black hole consists.

It’s an interesting simile to choose, to be sure. We can’t know what happened beyond her event horizon, from where nothing, unlike her flight home, can escape, not even light. Saying she needs time and space to recover spectacularly misses the point. Time and space don’t exist in a black hole.

And yet she is expected to perform to the requisite model of the freed exile. In some respects, this is an Old Testament trope. The entire historical Hebrew Bible can be viewed as a single, extended parable, the struggle of an ancient people to understand the mind of a god who is biddable, wrathful and vengeful. The Christian gospels offer very different parables.

Prodigal son

The prodigal son returns home to a joyful and loving welcome. At no point is he required to be grateful for that. The good Samaritan picks up and looks after the grievously assaulted traveller, who is never recorded as being required to offer thanks.

These stories – not least because they’re about men – should not be projected by other men (like me) on to Ratcliffe-Zaghari, any more than should be other narrative expectations of her. But they may be helpful for the rest of us.

The exile is placed beyond the reach of their own in worldly terms. For those of us of faith, there has to be a sure hope that they are never beyond the reach of their god. It follows that exiles not only owe no obeisance to their captors and oppressors, but also owe none to their liberators, who are simply agents of redemption on behalf of the divine.

And that principle, incidentally, applies whether we refer to the world’s exiles as refugees or immigrants, Ukrainians or Europeans, friends or strangers. Those are our identities, not theirs.

George Pitcher is a visiting fellow at the LSE and an Anglican priest

A version of this column appeared on Premier Christianity