MPs like Owen Paterson only know virtue if it pays

It used to be all about character, writes George Pitcher. Now they need to be told right from wrong.

One of the more intriguing aspects of Owen Paterson’s resignation as an MP is that he still persists in considering himself the victim of this affair. He is, he says, leaving “the cruel world of politics.” So he still thinks this is something that politics has done to him, rather than accepting what he has done to politics, which may be considerably more damaging.

To remind ourselves: Paterson was deemed guilty of taking considerable sums of money from private companies for lobbying the government on their behalf, after a painstaking two-year inquiry. The prime minister – who is currently Boris Johnson – sought to overturn Paterson’s consequent 30-day suspension from the House of Commons, by whipping his MPs to do so and aspiring to demolish the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority.

So ferocious was the backlash from all sides of the House that Johnson did what he does – he dumped his friend and changed his mind. This was described as a U-turn. In fact, technically it’s a reverse-ferret. Except it’s a very extreme version of a reverse-ferret. It’s like a ferret who has been trained at one of those anti-terrorism driving schools, where said ferret learns to reverse at 40mph and execute a handbrake turn before speeding away from the scene of the attempted crime.

Victim status

But it’s that victim status that Paterson claims which I want to interrogate. Events would seem to support that he genuinely believes in it – he wanted “to clear his name”. Had he just taken the 30-day rap, nobody much would have remembered it after a fortnight, friends could have said he’d acted honourably and he’d have returned quietly to take his parliamentary seat. It may have triggered a by-election, but he had a 23,000-odd majority in North Shropshire so he was hardly going to lose it.

What this must be about is self-entitlement on an ocean-going scale and, more importantly for my purposes here, an idea that public ethics are something that have to be made to stick by someone else, rather than applied by him to himself.

There is probably no greater recent political case study of how classical virtue ethics have been abandoned in public life in favour of selfish individualism. For the ancient Greek school of philosophy, personal character was essential for the good conduct of public life.

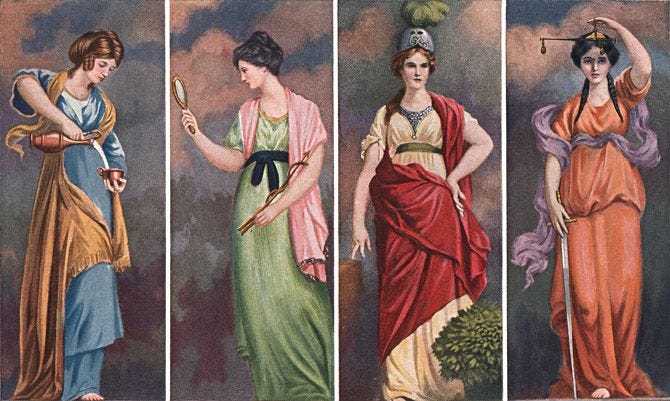

The four cardinal virtues were (and are) prudence, fortitude, temperance and justice. Paterson has exhibited none of these (and nor has his prime minister, but that goes without saying). Prudence – or wisdom, which Aristotle called the “nurse of the virtues” – discerns the right course of action at the right time. Fortitude is courage to know what is right and act on it (I speak here only of Paterson’s public life and not of his tragic family life).

Temperance is about self-control and provides sound judgment. And justice is about recognising what is fair and how that should be applied to those who depend on you.

Enlightenment

These virtues largely prevailed for centuries as a means of judging the behaviour of ourselves and others. Then came the Enlightenment of the 17th-18th centuries. Thinkers such as Rousseau, Kant and Mill replaced the responsibilities of people with that of the state, the person with the demos. The character of the individual was usurped by individualism.

It became a question of regulators and law-makers having to prove that we behave badly, rather than making that judgment ourselves. It simply would not occur to a public servant such as Paterson, for all his talk of “integrity”, that he should know what he should do rather than have someone else tell him.

Fault line

That is arguably a fault line that runs under today’s public square and causes regular tremors and occasional earthquakes, like the one we’ve just witnessed. We’ve needed a Richter scale for more than a decade now, since the MPs’ expenses scandal. That was a cast-iron example of how public servants could abandon self-examination in favour of an idea that someone else would tell them that it probably wasn’t really okay to have duck-houses and second homes for the family at taxpayers’ expense.

There is a direct line between MPs’ expenses and the Paterson debacle. It’s said that we get the politicians we deserve and to some extent that’s true. Johnson bets that his behaviour is already in the price and that, whatever he does, Conservative voters will buy it.

But at some stage there must be a reckoning, or Britain is headed towards its own Trump-like era of moral relativity. It’s just difficult to know what it would take. And until whatever it is arrives, we’re stuck with elected representatives who won’t recognise any private virtue in public life. Unless, of course, it pays them a hundred grand.

George Pitcher is a visiting fellow at the LSE and an Anglican priest.

I disagree. In fact I think this is a prejudiced, vituperative and dare I say unchristian view of the situation. The Commissioner’s investigation was unjust in that she did not want to hear evidence for the defence. She seems to have made her mind up well in advance, and may have been guided by her clearly left wing views. Paterson might well have played it differently but he chose to take the evidence of food adulteration directly to the department concerned. This is not influence-peddling, it is public spiritedness. He was not in breach of Parliamentary rules by having an advisory contract with these companies. The whole thing is a witch hunt by the press and the left.