Freedom to worship is at the heart of all liberty

The BBC Reith Lectures draw on Roosevelt's Four Freedoms, writes George Pitcher. But one of them spawns the others

Imagine, if you will, that a genie offered you one of four things: As much as you wanted to eat, everything you wanted to say or write, a courage that never dimmed, or access to God’s grace. What would you choose?

I’m guessing the canny are likely to choose the final option. Because, surely, that’s the only one through which you can have the whole set, if the worldly dice roll your way.

This idle speculation arises from this year’s BBC Reith Lectures, which instead of being four speeches delivered by a single luminary are four from different speakers, each of whom has taken as their theme one of FD Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms. These were named by the wartime US president in a speech in 1941 and are: Freedom of speech, freedom to worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear.

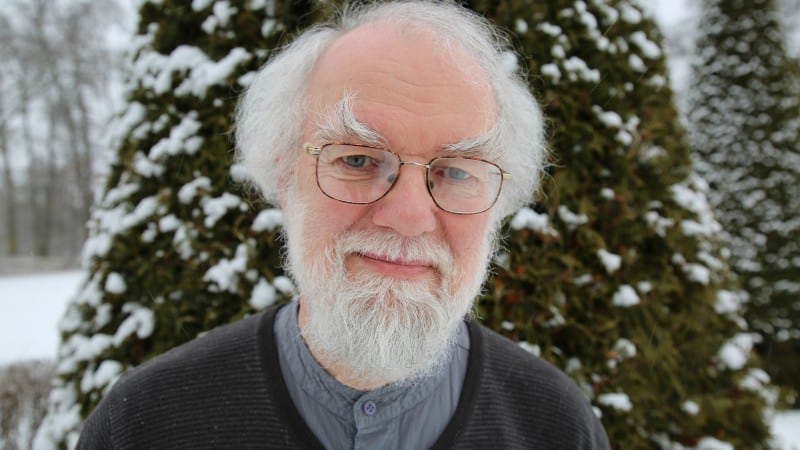

This week, the former archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, spoke on the freedom to worship, following on from the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s contribution on freedom of speech.

The more observant – in the literal rather than religious sense – will already have noticed that my opening analogy now doesn’t really stand up. Roosevelt specified that the core freedom in this regard is the right to worship, not the right to religious belief. That’s surely the difference between a public act and a private observance.

Outward enactment

No one ever prospered by trying to paraphrase Lord Williams, but I believe it’s fair to say that he wanted to conflate the two. Worship, he argued, is the outward enactment of the inner sense of our and others’ place in the world and how those places work and make sense in that world. Religious faith isn’t a personal and privatised thing; it only makes any sense in its collective enactment. And that is what has caused challenges historically for religious tolerance.

I particularly liked how this idea was teased out in the Q&A session afterwards by the chair, broadcaster Anita Anand. She said that Williams had talked about “lukewarm tolerance in a somewhat disparaging way.” She went on: “But I wonder whether the religious freedom you’re demanding can only exist in a pool of lukewarm tolerance because otherwise it’s the Goldilocks zone… it’s too hot or it’s too cold.”

Granny-flat view

Williams responded pretty robustly that the trouble with “lukewarmness is that it can be simply a patronising, marginalising strategy that says: ‘Well, if a few eccentrics are so determined to carry on these outmoded and outrageous practices and beliefs, we can probably squeeze them in somewhere and hope they die off.’ It’s the granny-flat view of religious tolerance.”

The granny flat view of a secular society is going to stay with me. But so is the idea of the robust versus the lukewarm. For the first time, this exchange made metaphorical sense for me of the words of the Book of Revelation, in which St John the Divine ascribes to the Christ these words addressed to the nascent Church of Laodicea: “Because you are lukewarm—neither hot nor cold—I am about to spit you out of my mouth.”

It’s this boldness and lack of apology with which the gospel is proclaimed that leads me to wonder where it takes us as one of Roosevelt’s key freedoms. To my mind, it leads from the front under that banner of freedom.

Freedom of speech

Adichie’s first Reith lecture dealt admirably with freedom of speech. The history of free speech in the Christian Church is not a proud one. As Williams noted, there have been periods in which the act of practising particular worship rites was not the only dangerous aspect of faith. Subscribing to the wrong doctrine could land you in mortal danger.

But the gospel is robust on such oppression. As the evangelist Matthew has it: “Do not be afraid of them, for nothing is hidden that will not be revealed, and nothing is secret that will not be made known. What I say to you in the dark, tell in the light, and what is whispered in your ear, proclaim from the housetops.”

As Williams maintained, that is a courtesy that we might usefully extend to other religions. So it’s not to say that Christian faith propagates the only free speech. But it is to say that it has it at its heart.

Liberating the poor

We await the Reith contributions from author and musician Darren McGarvey on freedom from want and foreign affairs expert Dr Fiona Hill on freedom from fear. Again, the Christian gospel is explicit on liberating the poor: “Whatever you do for the least of these you do for me.” And on fear, we’re called to be unafraid of what the world throws at us, because “they hated me before they hated you.”

This is not a contest. It’s not to say that Christian freedom beats up other freedoms. And it’s not to claim that if you buy one, you get three free. But it is to suggest that three of Roosevelt’s four freedoms derive from his second one, the freedom to worship.

Our Prayer Book has the seemingly self-contradictory line that to serve God “is perfect freedom.” That suggests a service that gifts all freedoms. And it’s a gift of grace from an authority somewhat higher even than either Lord Reith or President Roosevelt.

George Pitcher is a visiting fellow at the LSE and an Anglican priest.