Faith in the written word

Author Sarah Perry gives we religious hacks some hope, writes George Pitcher

If there’s one thing anyone who has ever written a novel can’t stand, it’s having to congratulate a successful novelist. So it’s through gritted teeth that I warmly welcome the words of Sarah Perry (The Essex Serpent) that religious faith is ceasing to be a subject of embarrassment in published fiction.

Not before time. Perry told the Edinburgh International Book Festival that, for her latest book Enlightenment, she was asked to put in more theology: “I assumed that everybody knew what the doctrine of predestination meant.” Bless.

The cause of my pathetic envy as I applaud her is that I had my first (and, to date, only) novel published in 2017, to almost universal disinterest. I like to tell people that it was well received – all three people who actually read it said they enjoyed it and only one of them was a family member. In truth, it did a bit better than that, but you get my drift.

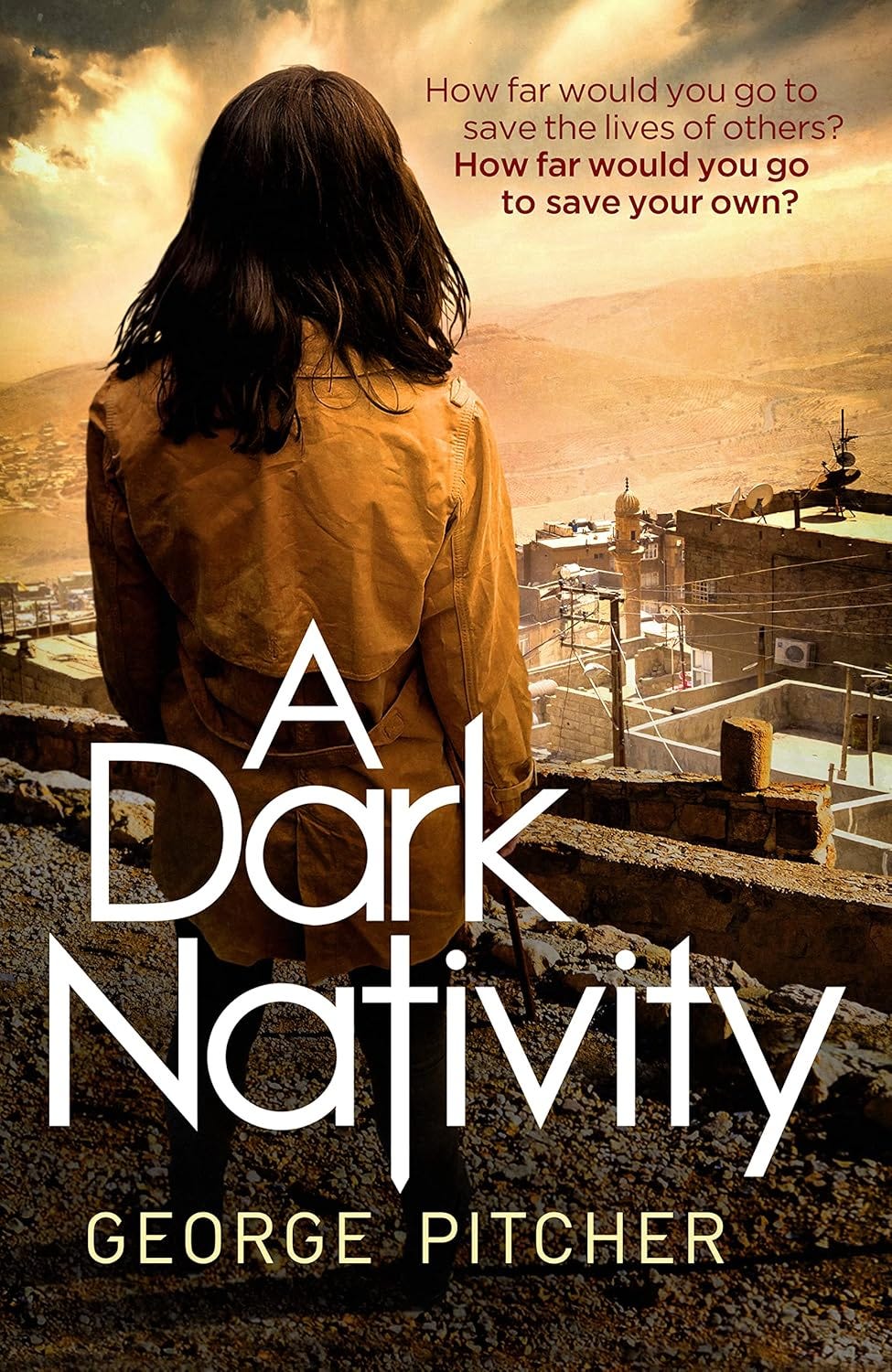

A Dark Nativity

It was an unashamedly religious psychological thriller, titled A Dark Nativity. Brace position, here comes the one-sentence synopsis: The narrator, Reverend Natalie Cross, is a frustrated former aid worker who undertakes a mission to Israel, is kidnapped and held hostage, murders her way to freedom, discovers she was the victim of an Anglo-American plot, wreaks her terrible revenge and (spoiler alert!) gives birth to a son of uncertain paternity.

See what I did there? As well as the latter-day nativity resonance, thematically I was interested in what redemption looks like in Israel and Palestine. I know, I know – but even I thought it would be distasteful to try to cash in on what’s happened there since.

Enough of this plug for a 7-year-old novel. My point is that its religious themes actively militated against it at the time. Novels addressing Christian faith occupied a particular publishing niche – a harsher word might be ghetto. To try to break out of it was pointless. The great Christian novelist Penelope Wilcock told me (very kindly) that my book was too religious for the secular market and too secular for religious readers.

Religion’s stylistic rules

The restricted area to which religion was confined had its stylistic rules. There was the cathedral close romp, which authors such as Catherine Fox had made their own. The vicarly whodunnit (lately updated by Reverend Richard Coles). Magic realism with its daemons and Philip Pullmans. And anything, in the wake of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, involving ancient monkish plots that might make a movie, with hooded figures walking in slo-mo through cloisters.

Vicars had to be either evil or silly. I may be both those things at times, but I’d like to think there is other stuff going on here worth cultural exploration. My narrator, Nat Cross, was driven, often funny and more than a little mad. So like a lot of Anglican clergy really.

Accepted in polite society

If she’s right – and I very much hope she is – it’s why what Perry has to say is so hopeful. Because it begins to suggest that religious faith will be accepted back into polite society. Whisper it softly, it might even become a cultural norm. If Richard Dawkins can describe himself as a “cultural Christian” and the historian Tom Holland, in his book Dominion, can claim that Christianity is the entire foundation of western civilisation, then there is everything to play for. And, indeed, write for.

It’s not as if cathedral frolics and the revelation of Jesus’s wife in Leonardo’s Last Supper was anything other than a fleeting fictional diversion of post-modernism. Religion and specifically Christianity had long been a staple of the novel in English before that.

Catholic guilt greats

I hesitate to mention their names in the same column as the authors above (including me, most obviously), but Graham Greene’s exposition of Catholic guilt in The End of the Affair and Evelyn Waugh’s of the impossibility of moral reformation in Brideshead Revisited are probably the best religious novels of the twentieth century.

Further back towards the birth of the English novel, the Reverend Edward Casaubon in George Eliot’s Middlemarch is perhaps the most tragic portrait of a clergyman who is neither evil nor silly. He stands, or sits pathetically, as a warning from history to today’s Church of England.

What we care about

And it’s to that, the established Church, that Perry’s remarks ultimately turn our attention. We’re told that there has been a five per cent spike in church attendance recently, but that of itself isn’t sufficient to suggest a renaissance in our religious culture. Our arts and culture will only ever really reflect what we care about.

Perry’s observation that faith is no longer a dirty word in publishing might yet suggest a reawakening of serious concern for its observation. If so, that’s good news for the religious, as well as for religious authors. And I might just get a sequel out of it.

George Pitcher is a visiting fellow at the LSE and an Anglican priest

A version of this column first appeared on Seen&Unseen