Assisted dying: Let's find our common ground

The new secularist views are far from profane, writes George Pitcher

The new spring for what we might call secular Christianity is strangely liberating for those of us of a more established or even orthodox faith.

So far, we’ve concentrated on what it means for the new secular Christians themselves. Richard Dawkins may (or may not) be a cultural Christian; Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s journey from Islam to atheism to Christianity may (or may not) be about defending the bulwark of western civilisation.

Authors such as Tom Holland and Justin Brierley trace the nourishment of that civilisation to Christian roots. Times columnist and atheist James Marriott notes a spiritual reawakening that makes us less secular than we think.

Step into secular debate

Pleasantly and surprisingly, all this gives those of us who self-identify as Christian a new opportunity to step into secular debate in a fresh and encouraging way. Take the debate over assisted dying, which has just returned to parliament (though not for a binding vote).

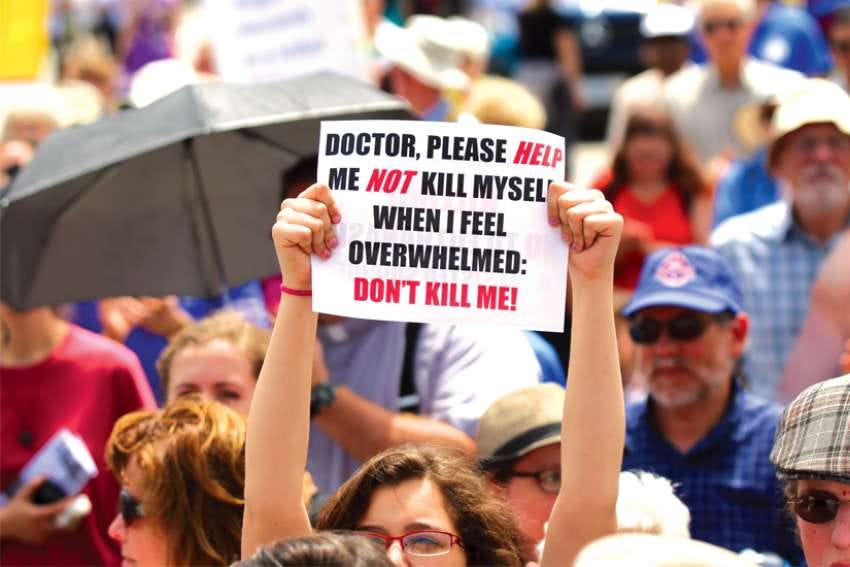

I am opposed vehemently to assisted suicide, or voluntary euthanasia. A decade ago, I couldn’t express my opinion on it without someone from the pro-lobby responding that my views, as a priest, are predicated on the “sanctity of life” (a phrase I have never used in this context) and consequently were irrelevant to anyone who doesn’t share my faith.

Lives worth more than others

In reality, my views on it are almost, if not entirely, secular. I believe it’s very dangerous indeed when the state sanctions in law the view that some lives are more worth living than others; that there are two tiers to human lives, those who should be protected and those who are disposable. I hold that the legal burden of proof of motive should be on those who assist a suicide, not on the state to prove that they acted coercively.

Question: No one can guarantee that assisted-suicide safeguards are watertight, so how many lives lost unnecessarily are deemed worth it for those who want assisted dying to have their way? One? 10? 100? More?

Matthew Parris’s revealing candour

I can’t know if it was his intention, but Matthew Parris seemed to do the case against assisted dying no end of good recently, by writing the secular case for it with disarming and revealing candour. What was wrong with people deciding they were a burden on their families and the economy when they thought their time had come?

I suspect many in the euthanasia movement held their heads in their hands at that, for it is exactly the dystopian future to which they promise they’re not taking us.

But what the new secular Christian consensus has brought is a common ground on which we can all debate more calmly. As I say, it’s not so long ago that some of those who profess to support dignity in dying were posting that they hoped I would die an agonising cancerous death.

What dignified discussion looks like

What a more dignified secular discussion of assisted suicide, which can include people of faith, looks like is this: Alice Thomson writing in the Times that she’s changed her mind from supporting it, having witnessed the harms that have occurred from it on other jurisdictions, because she “doesn’t want to hasten anyone else’s death”.

It looks like Rachel Clarke, the palliative care doctor and author on whom the ITV covid drama Breathtaking was based, revealing in the Guardian that the issues on the frontline are hugely complex and less about whether suffering at ends of life should be about assisted dying than scant resources to relieve that suffering.

It also looks like Amy Bloom, writing with great dignity about taking her husband, diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, to die at Dignitas in Switzerland, a book that’s hard to read, principally because of the tears in the eyes. And, yes, it looks like the honesty that Parris brings to the party.

My vulnerable argument

I used to write that I was surprised and disappointed that those who debated me on assisted suicide seldom if ever took me into a more fruitful area and one in which my opposition to assisted dying would be most vulnerable. Since medical science means that we’re living longer and consequently subject to many more degenerative life conditions, what are my proposed solutions to intolerable suffering?

My usual response historically would be that palliative care, of Clarke’s sort, is advancing at such a pace that we shouldn’t jeopardise it by offering assisted suicide as a treatment option (or opt-out); fairly soon, we will have reached a place where no one, outside a trauma ward, need die a bad death.

But that’s not good enough in the new debate. We really need to address what we want in our society from end-of-life care. We must address the liberation of doctors from the prospect of ruinous litigation for allowing patients to die comfortably when their time has come, without officious interventions.

That doesn’t mean helping to kill them, it means letting them die. Big moral distinction. We can surely all meet in this place, people of faith and none, and agree that we’re honouring the sanctity of life in our own ways.

George Pitcher is a visiting fellow at the LSE and an Anglican priest

I agree George that it should be possible to find common ground, especially as we in the rich world are living longer lives and, many of us, facing protracted deaths. I also “identify as Christian”, as you put it, and have always been vehemently opposed to the idea of euthanasia, however it’s dressed up. But I am also mindful of my late Uncle John, a devout Catholic and a truly dedicated doctor. He toiled for many years as the only GP in a poor extremely tough part of south London. He had inevitably an unsentimental view of death. I was staying with him one very cold new year when I was 15, and found him eating his breakfast at 8 am, having been out on his frozen rounds since 5. “Six of the old people died during the night,” he said laconically while reading the Times. I was of course shocked. “Well,” he said, glancing up briefly, “it’s normal for this sort of weather.” This led, a day or two later, to a chat about easing people’s passing. He told me about what he called the Brompton cocktail, a blend of morphine and cocaine. He had been taught as a student to administer it as a painkiller for patients in extremis. “Of course you know it will kill them eventually, probably on the second or third injection, but the point is you’re not trying to kill them, you’re hoping to make them more comfortable.”

The lesson in that is that, as you say, we need to take palliative care much more seriously.